Ah, yes, about the eschaton and pesher — I will tell you how I got there. I was wondering about the theory that the Bible was written not only as a historical account but as a prophecy of the end times as well — specifically the parts that do not specifically apply to the end time. Actually, I was questioning whether that was true. I know people who think we have arrived at the end time. But I don’t believe anyone can know when that time arrives. Thus, prophecying that it is coming soon, is falling into a pattern of other times when someone steps up to declare that this time of war and plague is the end of the world.

So, I went back to a book I recently read about misreading scripture with western eyes, because I recalled a chapter — “God’s Endtime will Happen in my Lifetime.” And I read something I had missed, but it answered my questions. First, let’s look at a couple of word meanings:

- eschaton: the final event in the divine plan; the end of the world. (from Greek word meaning “last”). Hugh Nibley often talks about eschatology.

- pesher: to interpret (Hebrew)

Here is a quote from that chapter:

Why do Westerners seem convinced that Christ will come on our watch? The truth is, we aren’t the first. The Dead Sea Scrolls are copies of Old Testament books discovered near Qumran, the commune of the Essenes on the rim of the Dead Sea. This reclusive group of Jews from Jesus’ day had several peculiarities. One of the lesser known was a method of biblical interpretation that scholars often call pesher. This method of interpretation requires two presuppositions. First, it assumes a verse of Scripture is referring to the end of time, even if it doesn’t originally appear to be. For example:

- For behold, I am raising up the Chaldeans, That fierce and impetuous people Who march throughout the earth To seize dwelling places which are not theirs. (Hab 1:6 nasb)

Habakkuk refers to the Chaldeans as fierce warriors sweeping away all in their path. Yet God has marked them for judgment (Hab 1:12). This passage seems to be referring to Chaldeans who were threatening God’s people in Habakkuk’s day. The Essenes begged to differ. The pesher exegetes insisted the verse is actually referring to the eschaton. Second—and this is the most important ingredient—the pesher exegete interprets his or her current time as the eschaton.

Thus, step one is assuming a given passage is actually about the end of time; step two is assuming that time is now. The folks at Qumran interpreted the passage above this way; they believed Habakkuk was actually talking about the end of time, whether he knew it or not. Trouble is, the Chaldean threat is long gone. But pesher exegetes are nothing if not determined. The Essenes reasoned that the term Chaldeans was really code for Chittim, who had the famed warships made from pine trees on Cyprus. They then expanded the meaning of Chittim (Cyprus) to include all of Greece (and eventually Rome). God’s people were warned that the ships of Chittim would come to attack (“And ships shall come from the coast of Chittim,” Num 24:24 kjv). Therefore, God’s people needed to take notice when Roman warships landed to attack. Fear not! For Habakkuk has foretold that God would smite the Romans and give victory to his people (the folks at Qumran). (Richards, E. Randolph; O’Brien, Brandon J.. Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes . InterVarsity Press. Kindle Edition.)

I can’t really say whether we can take scripture that was an oral history for a particular time frame and then assign it to a new time frame — replacing ancient people and countries with our current people and countries. And although the Essenes did it and believed it; believing that they were living in the end time — the end time did not come in their lifetime. So, it is not a foolproof method of determining if you are going to be living when the messiah returns. But people sure love to make predictions, and this seems to be the case since the world began. I have to agree with the authors that used these three parables of Jesus —

The servant who was ready when his master showed up was blessed: makarios (Lk 12:37-38). When his disciples asked about the end, Jesus told three parables in a row (Mt 24:3). The first warned that the master could come at any time, “So you also must be ready, because the Son of Man will come at an hour when you do not expect him” (Mt 24:44). The second parable warned it could be sooner than we think (Mt 24:50). The third parable warned it could be later than we think (Mt 25:5). Jesus’ point seems clear. Jesus has covered all the bases: could be sooner, could be later. The first parable carried the main point: Jesus “will come at an hour when you do not expect him.” Yet we never seem to weary of guessing. (Richards, E. Randolph; O’Brien, Brandon J.. Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes . InterVarsity Press. Kindle Edition.)

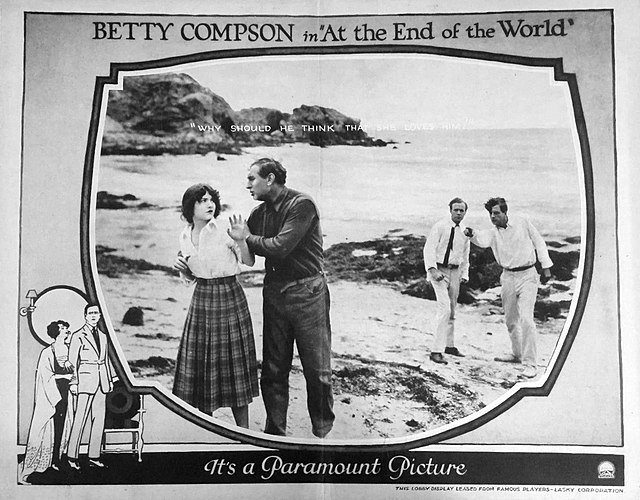

You’ve got to love the theme though — as these two actors exemplify the never-ending end of the world genre film of 1921: