“Long before the Christian Church was ever heard of, people throughout the world celebrated one great festival that far overshadowed all other social activities in importance. That was the great Year Rite, the celebration of the creation of the world and the dramatization of a plan for overcoming the bondage of death.

It took place at the turn of the year when the sun, having reached its lowest point on the meridian, was found on a joyful day to be miraculously mounting again in its course; it was a day of promise and reassurance, heralding a new creation and a new age. Everywhere the great year festival was regarded as the birthday of the whole human race and was a time of divination and prophecy, marked by a feast of abundance in which all gave and received gifts as an earnest hope of good things to come.

There is plenty of evidence in the early Christian writings that Christ was born not at the solstice but in the spring, early in April. Much has been written on the shifting of his birthday celebration to make it coincide with the day of Sol Invictus, a late Romanized version of an oriental midwinter rite. In other parts of the world, people had no difficulty identifying the Lord’s birthday with the greatest of popular festivals.

When Pope Zacharias rebuked the Germans on the Rhine for their pagan festival at midwinter, Boniface could answer him back, that if he objected to heathen feasts and games, all he had to do was look around him at Rome, where he would see the same feasting, drinking, and games on the same ancient holy days to celebrate the same blessed event—he was referring, of course, to the Saturnalia, the great prehistoric festival of the Romans. Our own Yule, carols, lights, greenery, gifts, and games are evidence enough that a northern Christmas is no importation from the East in Christian times but something far older.

Now, there is no law of the mind that requires all men everywhere to put just one peculiar interpretation on the descent and return of the sun in its course. This complex and specialized festival, which follows so closely the same elaborate pattern in Babylonia, Egypt, Iceland, and Rome, is now recognized to be no spontaneous invention of untutored minds but the remnant of a single tradition ultimately traceable to one common lost source.

The essential feature of this great world festival everywhere is that it aims, if but for a few short days, to recapture the freedom, love, equality, abundance, joy, and light of a Golden Age, a dimly remembered but blessed time in the beginning when all creatures lived together in innocence without fear or enmity, when the heavens poured forth ceaseless bounty, and all men were brothers under the loving rule of the King and Creator of all.

Is it at all surprising that the Christian world’s celebration of the Savior’s birth should fall easily and naturally into the pattern of the older rites? In the end they are really the same thing—both are recollections of forgotten dispensations of the Gospel; both are attempts to recall an age of lost innocence and lost blessings.

Lost? Who can doubt it? There is a nostalgic sadness about Christmas, as there is about the Middle Ages, with their everlasting quest of something that has been lost. Christmas is a small light in a great darkness; it is evidence of things not seen. It is not the real thing but the expression of a wish, for like the great year rites of the ancients, it merely dramatizes what once was and what men feel they can still hope for.

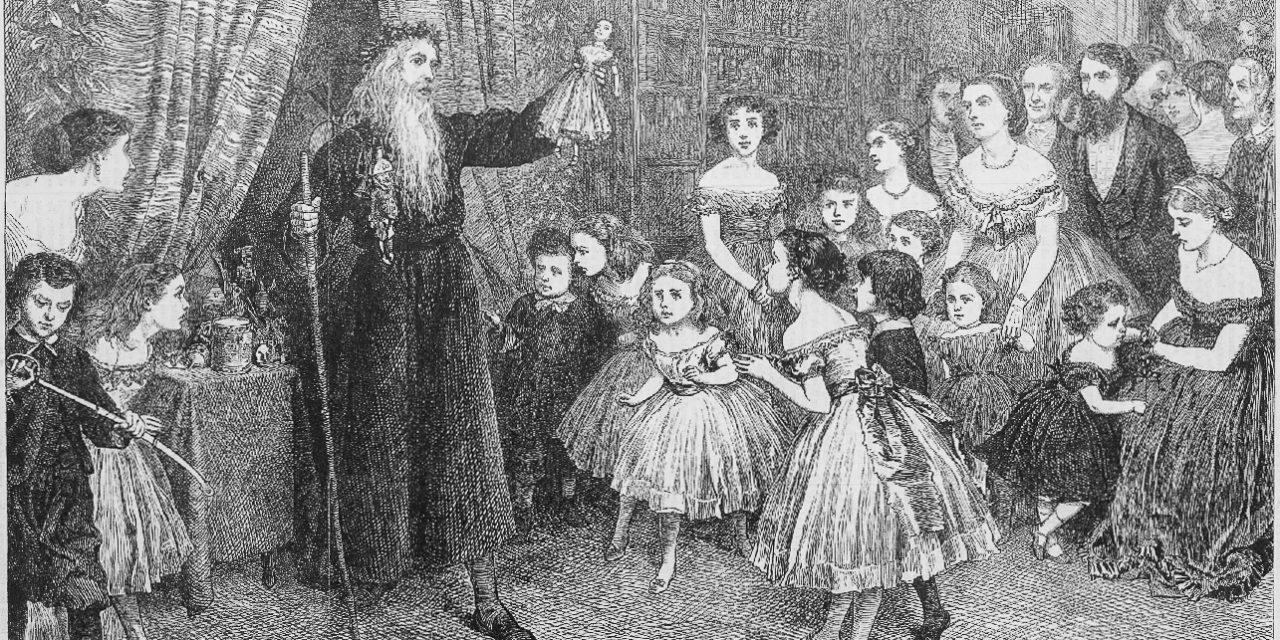

A brief, brave show of generosity and cheer is our assurance that earth can be fair, and we gladly join with all mankind in the gesture. In so doing we would remind the world that Christmas is both a demonstration of man’s capacity for enjoying good and sharing it and of his helplessness to supply it from his own resources. The great blessings we seek at Christmas are not of our own making (the everyday world is our handiwork) but must come from another world, even as Father Christmas comes to the children as a visitor from afar.

The painful fact that Christmas has an end and “all things return to their former state” is an adequate commentary on the actual state of things. The world, which denies revelation, once a year has a moment of lucidity in which men are permitted to hope; then it returns to its old disastrous routine—but because of Christmas that routine can never be the same.

For men have allowed themselves to be caught off guard, for a brief moment they have let down the barriers and shown where their hearts really lie; Scrooge the man of business can never go back again after his Christmas fling—however ashamed he may be of it in the cold light of day, it is too late to deny that he has shown Scrooge the man of the world to be but a mask and an illusion.

So the Latter-day Saints have always been the greatest advocates of the Christmas spirit; nay, they have shocked and alarmed the world by insisting on recognizing as a real power, what the world prefers to regard as a pretty sentiment. Where the seasonal and formal aspect of Christmas is everything, it becomes a hollow mockery.

If men really want what they say they do, we have it, but faced with accepting a real Savior who has really spoken with men, they draw back, nervous and ill at ease. In the end lights, tinsel, and sentimentality are safer, but a sense of possibilities still rankles, so to that we shall continue to appeal. For by celebrating Christmas the world serves notice that it is still looking for the Gospel.”

This article originally appeared in Millennial Star 112/1 (January 1950), 4-5. It was reprinted in Eloquent Witness: Nibley on Himself, Others, and the Temple, edited by Stephen D. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 17 (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2008), 121-124.