I’ve been reading about pandemics since we’re in the middle of SARS-CoV-2 — the novel coronavirus of 2019 — named by the World Health Organization (WHO) on February 11, 2020, and first identified in Wuhan, China. The virus probably came from a bat — either the wet market in Wuhan, or it escaped from their virus lab in Wuhan — the Wuhan Institute of Virology biolab. I think it escaped the lab — that patient zero worked in the lab. The virus was probably detected in late November or early December, thus it is dated 2019 (also called Covid-19.) It was first called the Wuhan Virus, but China didn’t want to be identified with this novel virus and people said it was racist to call it the China Virus or Wuhan Virus. So it got a new name. However, it’s important to trace a new disease to its origin — this is part of learning and controlling the disease. It’s not party politics. It’s not racist.

As I began reading about the Spanish flu of 1918, I found an article written in the National Geographic on January 24, 2014, that suggested the Spanish flu originated in China. China. Yep. How strange.

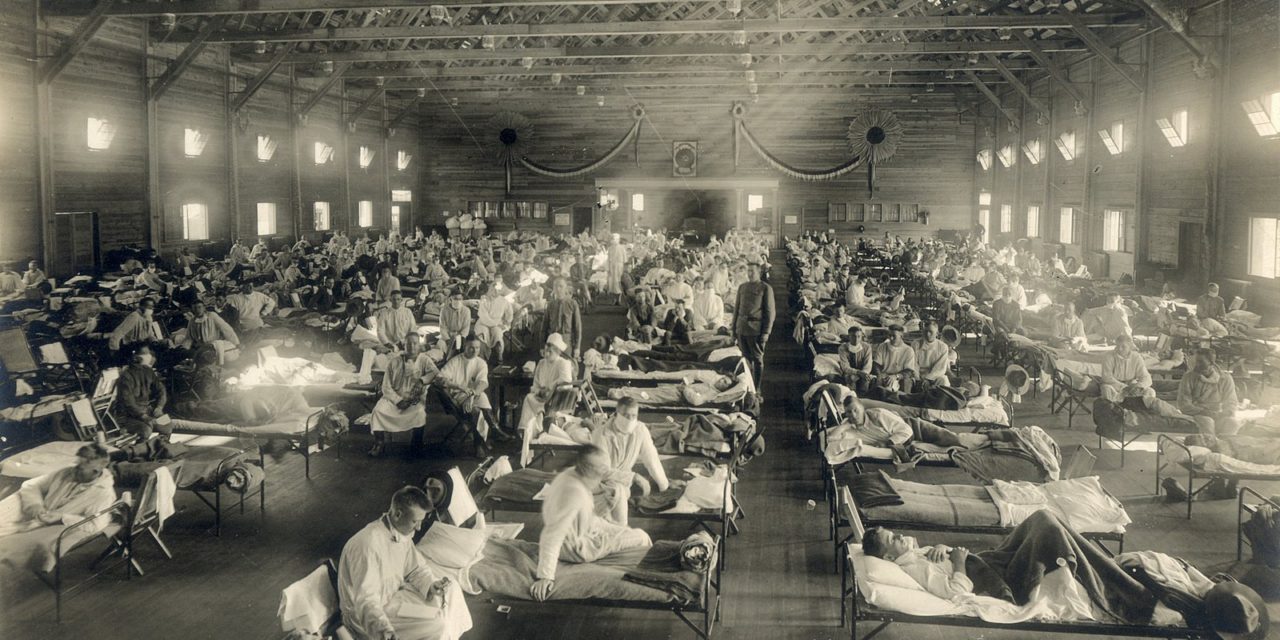

For decades, scientists have debated where in the world the pandemic started, variously pinpointing its origins in France, China, the American Midwest, and beyond. Without a clear location, scientists have lacked a complete picture of the conditions that bred the disease and factors that might lead to similar outbreaks in the future.

It’s important to know where a virus originates. It helps us understand how to control a pandemic –now, in the past, and the future.

Chinese Labor Corps of World War I

World War I began on July 28, 1914, ending on November 11, 1918. The Spanish flu most likely emerged in the winter of 1917 — plenty of time for the flu to spread via a labor corp. “The deadly “Spanish flu” claimed more lives than World War I, which ended the same year the pandemic struck.” Approximately 10 million people died in World War I, whereas about 50 million people died in the Spanish flu.

New research is placing the flu’s emergence in a forgotten episode of World War I: the shipment of Chinese laborers across Canada in sealed train cars. (Humphries, Mark. 1918 Flu Pandemic That Killed 50 Million Originated in China, Historians Say: Chinese laborers transported across Canada thought to be source, National Geographic, Janurary 24, 2014)

The historian, Mark Humphries discovered records documenting that 96,000 sick Chinese laborers were brought in to work behind the British and French lines on World War I’s Western Front which may have caused the spread of the Spanish influenza of 1918:

A multidisciplinary perspective combined with new research in British and Canadian archives reveals that the 1918 flu most likely emerged first in China in the winter of 1917–18, diffusing across the world as previously isolated populations came into contact with one another on the battlefields of Europe. (Paths of Infection: The First World War and the Origins of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, Mark Osborne Humphries)

Humphries found archived data about a respiratory illness that hit northern China in November 1917. Chinese health officials identified it as the Spanish flu. Records also showed that 3,000 of the 25,000 Chinese laborers who were transported by train in Canada in 1917 became sick. You can imagine the close quarters on a train. They were quarantined with flu symptoms.

Although China declared war on Germany, they never sent troops to fight because the Allied Powers did not want them to join the fight (especially Japan). But China’s President Shikai found a way to become involved:

China couldn’t fight directly, Shikai’s advisors decided, the next-best option was a secret show of support toward the Allies: they would send voluntary non-combatant workers, largely from Shandong, to embattled Allied countries.

Starting in late 1916, China began shipping out thousands of men to Britain, France and Russia. Those laborers would repair tanks, assemble shells, transport supplies and munitions, and help to literally reshape the war’s battle sites. Since China was officially neutral, commercial businesses were formed to provide the labor, writes Keith Jeffery in 1916: A Global History. (Smithsonian Magazine)

Why was it called the Spanish flu of 1918?

It was not because the flu started in Spain. Not at all. It has to do with World War I –Spain was neutral. Spain could, therefore, report in the media all the details of the flu. Allied and Central Powers suppressed media about the flu to prevent the decline of moral.

News of the sickness first made headlines in Madrid in late-May 1918, and coverage only increased after the Spanish King Alfonso XIII came down with a nasty case a week later. Since nations undergoing a media blackout could only read in depth accounts from Spanish news sources, they naturally assumed that the country was the pandemic’s ground zero. The Spanish, meanwhile, believed the virus had spread to them from France, so they took to calling it the “French Flu.” (History.com)

I get it. No one wants to be blamed for starting an epidemic. I wouldn’t want to be known for the one that inadvertently passed the flu virus to my grandma (I would feel terrible.) However, if we want to understand viruses we have to be willing to trace their origins and be transparent. That’s probably going to be difficult in a world that does not care about the truth.

Further Reading: