I actually have listened to this one quite a bit, it’s called But What Kind of Work? Nibley talks about what we should be doing on earth — its quite a fun listen or read, as Nibley’s sense of humor comes through. As you read through the list, some of it sounds familiar to washing and anointing — the initiatory principles.

“These are the gifts and talents that prescribe our proper activities on this earth (there are usually seven or twelve, the cosmic numbers):

1. First of all, before anything can happen, one must be aware of being in the world. A measure of awareness is apparently possessed by all living things, and the greater the awareness, the greater the intelligence. If our time here is to have any meaning at all, our brain and intellect must be clear and active; otherwise, we might as well send bags of sand through the endowment while running up the most satisfying statistics on our computers. This is, of course, the most exhilarating aspect of the whole thing–our life here, a constant mental exercise, the purest form of fun, with a minimum of mechanization.

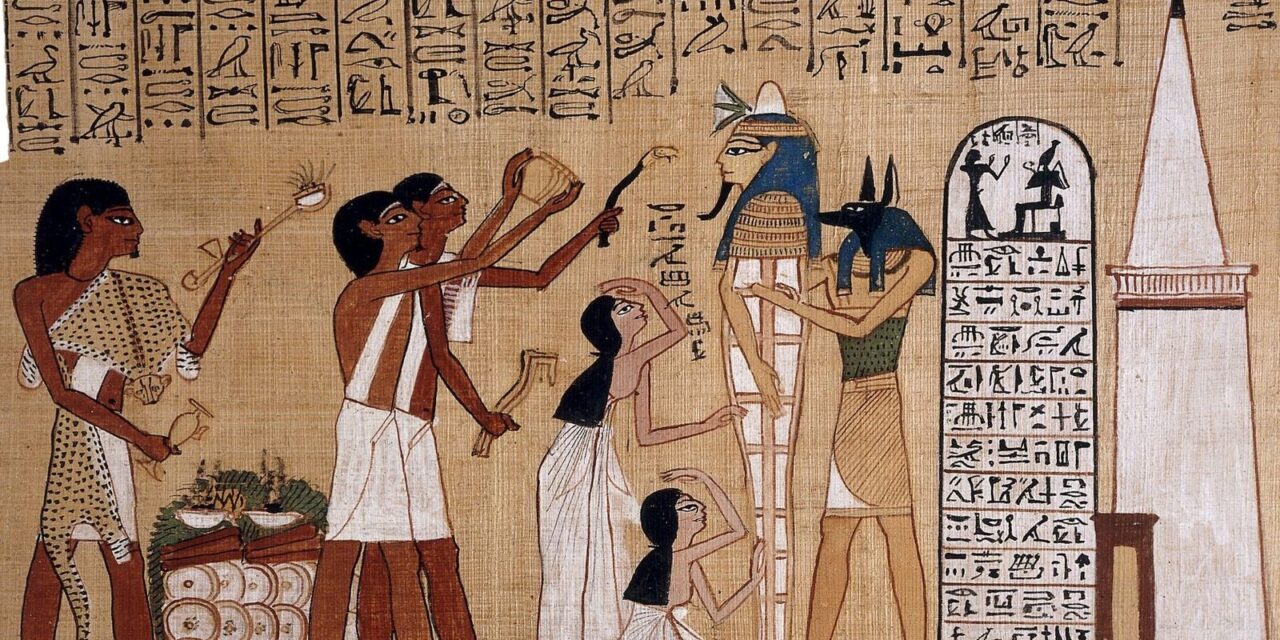

2. In this life we have too many options. There are thousands of good things any of us could be doing at this moment but will never be allowed to do, because of the shortness of time and the peculiar need we have to focus on just one thing at a time. As I lie in my bed and gaze at the shelf-lined wall of my room, I suffer pangs of frustration, seeing there a wondrous array of books which I have spent many years preparing to read and gleefully collecting in dusty bookstores of Europe and America. But now, just as I am able to handle the stuff, I must forego the temptation and the delight because there is other work at hand–it’s the Egyptian stuff that will keep me going me the rest of my days. What can any of us do in such a predicament? We can only “hear the word of the Lord,” and to hear is to obey; that is why the Egyptian Opening of the Mouth actually begins with the ears. From the very first amid a million possible paths we are lost and bumbling without God’s instructions; and in fact both his works and his words are for our benefit (Moses 1:38-39), the words always going along with the works to put us into the picture: “My works are without end, and also my words, for they never cease” (Moses 1:4).

3. Next is the eye, a positive obsession with the Egyptians and the Hebrews (they called Abraham “the Eye of the World”), who believed that it commands the data necessary for a comprehension of the structure of the cosmos itself. “The eye cannot choose but see,” and what it sees is the big picture–it gauges and measures, perceiving ratios and proportions and noting those that are pleasing and those that are not, and it compares and structures all by the awareness of light, the constant and the measure of all things. The word intelligence is from inter-legere, meaning to make a selection between things, to put a number of things together and to classify, to view the situation and to make a decision; and to make a decision is to discern–the brain and intellect must have something to work with, data that comes mostly by sight.

4. Being aware, instructed, and informed does not complete a fullness of joy, we are told, which can come only when spirit is united with the body. The enjoyment of the senses, says Brigham Young, is one of our greatest privileges upon this earth. The most primitive and primary of senses, we are told, and the one in which the Egyptians find the liveliest earthly sensations and delights, is the sense of smell, being most closely tied to emotion and memory, as well as to the delights of taste and touch. If an important aspect of our sojourn here is the release of tension, monotony, and drabness by those sensual delights best represented by the nose, it is the disciplined taste, smell, and touch as well as hearing and seeing that have, as Brigham Young again informs us, the greatest capacity for enjoyment; and discipline means control. Appetites, desires, and passions can give us the best of what they have to offer only if they are kept within the bounds the Lord has set. Beyond those bounds they become surfeit and corruption, and the source of almost every unpleasant sensation. By a clear and definitive statement, we are saved from wandering everlastingly amid moral quandaries and probabilistic exercises such as the endless debates of the doctors and schoolmen on just how naughty is naughty.

5. We are never alone; we share a universe of discourse through the miracle of the word. Again we quote a favorite passage: “There is no end to my works, neither to my words” (Moses 1:4). “Behold, this is my work and my glory,” namely, to share with others what he has, “to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man” (Moses 1:38-39). There is nothing mysterious about the endlessly debated logos–it is communication. God does not choose to live in a vacuum. Nothing is said about the mouth as eating, and indeed the Lord says that what goes into the mouth is not the important thing but what comes out of it; for it is that which puts us into touch with each other.

Back to the Egyptians and the Hebrews. Those two oldest books in the world which we mentioned, both contain the same peculiar doctrine of the Word. According to this, we have “the seven gates of the head,” the openings–eyes, ears, nostrils, and mouth, which are the receptors by which we take in all the data that come to us in various energy packages from the outer world. In the mind, the brain, and the heart, so goes the doctrine, this data is processed, sorted, interpreted, and given form and meaning; but though we have seven receptors, there is only one projector, and that is the mouth. By word of mouth alone do we communicate with others to discover how closely our idea of the world matches theirs, thereby assuring ourselves that our world must indeed have an objective basis in reality. You must take my word for it that I see and hear what I say I see and hear, and therefore if I wish, I can so easily confuse you by spreading false reports that all values and relationships become confounded. Satan is the Author of Confusion, the Father of Lies, the Deceiver, “the fiend who lies like truth,” and he does all of his work by distortion of the word, the systematic study of the ambitious rhetorician, lawyer, salesman, and politician. What God asks of the mouth and lips, therefore, is not that they eat the proper food–they have means of sensing that–but that they never speak guile!

6. It is essential while we are moving among the properties and characters of our earthly drama that we deport ourselves properly and keep our physical plant in top form, upright and alert. They used to make a big thing of the Posture Parade at the BYU, and I always used to wonder why my grade-school teachers made such a fetish of “holding your head up.” The ancients considered the neck as the tower, a sort of control on the rest of the body, the index of confidence and courage. It is the characteristic mark of the alert and healthy animal. All the basic signs for vitality in Egyptian depict the neck and esophagus. Let us not underestimate, as I long did, the importance of the neck in keeping the whole body properly in line.

7. You can expect to have trials and burdens not a few, for that is part of the game; and for that your shoulders and back should be strong–those burdens are necessary to the plan and are meant to be borne. Best of all, they will not hurt you! The kings of old did not disdain to represent themselves carrying loads of brick on their backs for the building of the temple.

8. Along with that, you are to be valiant; mere innocence is not enough, as Brother Brigham said, if you are to realize your potential. The ancient formula blesses the arms to be strong in wielding the symbolic sword of righteousness. At any rate, passivity is not for you; you must expect and prepare to face opposition, stiff opposition, head-on. And the Saints have always had more than their share of that.

9. Besides the brain, the phrenos, the ancients considered the thumos, the breast, the main receptacle and processor of our feelings and emotions. It is there that the surges of passion or fear are felt, and it is there that our prevailing attitude to things is engendered. If it is important for our words, our rational and objective intercourse, to be absolutely guileless, it is equally important that our feelings be pure and virtuous, for any other feelings are necessarily false and pernicious–what possible use or excuse can there be for them?

10. As to our reins (kidneys) and liver, you leave your innards alone; they should perform their proper function on their own, and the less they attract our attention, or anyone else’s, the better! It is interesting that the less people are doing in the building of the kingdom or in seeking light and knowledge, the more they worry about their bodily functions, as our TV commercials amply attest.

11. The Hebrew and Egyptian rites place one goal and one delight above all others, the joy in one’s posterity, in patriarchal succession. Everywhere, both people give us to understand that the ultimate delight is to be in the company of one’s own flesh and blood. As Wilhelm Busch in one of the best-known lines in German literature informs us, it is not difficult to become a father, it may even be pleasant, but it is the result that is the wonder and glory and burden of our existence. Another quality we share with God.

12. Lastly comes our means of getting around in the world, feet and legs. The Egyptians place great emphasis on this; the resurrection is finally achieved only when the legs are set in motion on the path of eternity. As to Abraham, the official title of his biography, whether in the Bible or the Apocrypha, is lech lecha, “Get up and get going!” and so he did, a wanderer and a stranger until the end of his life. The Saints are the most mobile of mortals, das wandernde Gottesvolk (God’s wandering people), like Abraham, strangers and pilgrims, but missionaries in the world, meant to circulate abroad, to get around and broadcast the good news and spread the stakes of Zion. [From Approaching Zion. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley, vol. 9 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, and Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1989), pp. 265-270].