A few years ago while researching a topic, I read someone’s opinionated religious talk. I was embarrassed for him. Because he was so dogmatic about opinions he claimed were facts. Yet, they could be argued as not true. And yet, he said if you believed otherwise, it was a heresy, and you were wrong and doomed for destruction. He published a book that was later rescinded because of similar statements.

Most of us, at times, can be overly certain and opinionated. We think we are correct, that our perspective is the truth, and therefore we can act boldly and not even entertain the idea that perhaps we are wrong. Or perhaps it is not necessary to slam the other person.

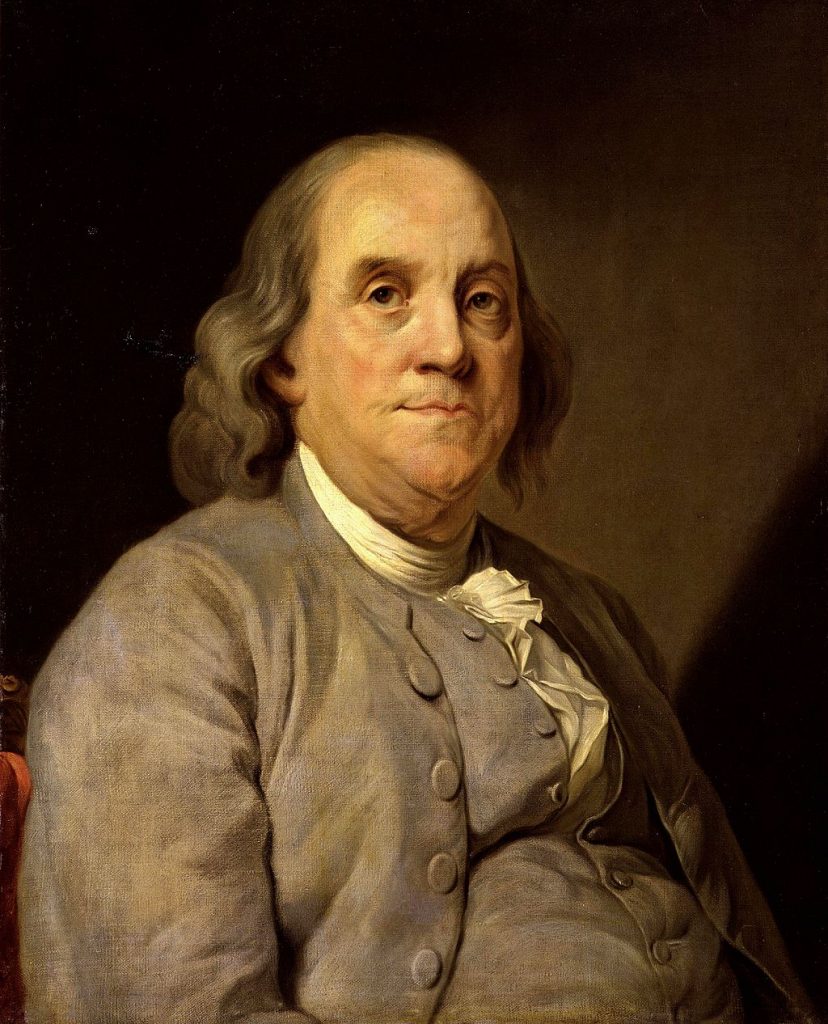

Being dogmatic is probably being prideful. It made me think of some good advice from Benjamin Franklin.

Benjamin Franklin was once accused of being dogmatic and overly opinionated.

But Franklin took the criticism and thought about it. He decided to add it to his list of virtues — a list of things he was working on to improve his character:

My list of virtues contain’d at first but twelve; but a Quaker friend having kindly informed me that I was generally thought proud; that my pride show’d itself frequently in conversation; that I was not content with being in the right when discussing any point, but was overbearing, and rather insolent, of which he convinc’d me by mentioning several instances; I determined endeavouring to cure myself, if I could, of this vice or folly among the rest, and I added Humility to my list, giving an extensive meaning to the word.

Therefore, Benjamin Franklin decided to make some changes in the way he disagreed with people.

I cannot boast of much success in acquiring the reality of this virtue, but I had a good deal with regard to the appearance of it. I made it a rule to forbear all direct contradiction to the sentiments of others, and all positive assertion of my own. I even forbid myself, agreeably to the old laws of our Junto, the use of every word or expression in the language that imported a fix’d opinion, such as certainly, undoubtedly, etc., and I adopted, instead of them, I conceive, I apprehend, or I imagine a thing to be so or so; or it so appears to me at present.

When another asserted something that I thought an error, I deny’d myself the pleasure of contradicting him abruptly, and of showing immediately some absurdity in his proposition; and in answering I began by observing that in certain cases or circumstances his opinion would be right, but in the present case there appear’d or seem’d to me some difference, etc.

Franklin found advantages in this new way of conversing with others.

I soon found the advantage of this change in my manner; the conversations I engag’d in went on more pleasantly. The modest way in which I propos’d my opinions procur’d them a readier reception and less contradiction; I had less mortification when I was found to be in the wrong, and I more easily prevail’d with others to give up their mistakes and join with me when I happened to be in the right.

And this mode, which I at first put on with some violence to natural inclination, became at length so easy, and so habitual to me, that perhaps for these fifty years past no one has ever heard a dogmatical expression escape me. And to this habit (after my character of integrity) I think it principally owing that I had early so much weight with my fellow-citizens when I proposed new institutions, or alterations in the old, and so much influence in public councils when I became a member; for I was but a bad speaker, never eloquent, subject to much hesitation in my choice of words, hardly correct in language, and yet I generally carried my points.

The Pride Problem

In reality, there is, perhaps, no one of our natural passions so hard to subdue as pride. Disguise it, struggle with it, beat it down, stifle it, mortify it as much as one pleases, it is still alive, and will every now and then peep out and show itself; you will see it, perhaps, often in this history; for, even if I could conceive that I had compleatly overcome it, I should probably be proud of my humility. (The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin)

What it means to be Dogmatic

I became curious about what dogmatic means: “dogmatic: inclined to lay down principles as incontrovertibly true.”(ref)

The Cambridge Dictionary explains — “If you are dogmatic, you are certain that you are right and that everyone else is wrong.”

But Can you change your way?

The brain is plastic, meaning we are teachable and can change, but it takes effort — like everything.

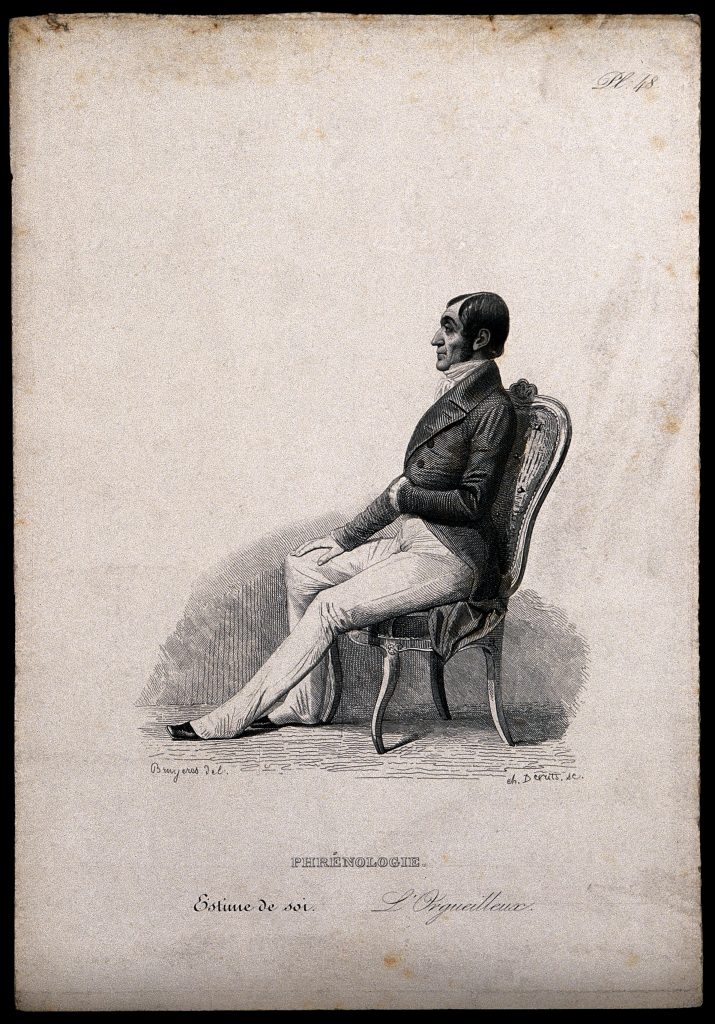

A man sitting erect on a chair; representing pride as a type

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

images@wellcome.ac.uk

http://wellcomeimages.org

A man sitting erect on a chair; representing pride as a type of the ‘sentiment’ of self-esteem, a phrenological ‘faculty.’ Steel engraving by C. Devrits, 1847, after H. Bruyères.

1847 By: Hippolyte Bruyèresafter: Charles DevritsPublished: 1847

Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only license CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Updated. Originally posted March 2018.